+3 more

At 7,010 m (23,000 ft), Khan Tengri is situated on the borders of Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan and China and has a reputation for its difficulty due to severe weather patterns that originate in the surrounding regions of Siberia and the Taklamakan desert. With high UV exposure and unpredictable weather at play, Ventile® Cotton accompanied the team on the ascent, making this the highest known point of elevation a Varsity cap has ever seen. We sat down with Jørgen to hear more about the journey, including the preparation and impact the expedition has had on him afterwards.

I was actually first connected to the expedition when I was interviewed on a podcast run by two of the other expedition members. We got deep into conversations about mountains. Somewhere in that discussion, they mentioned they were heading to Khan Tengri with the American Climber Science Program and “The Indiana Jones of Climate Science”, Dr. John All. Dr. All is a geoscientist and has undertaken many expeditions around the world, including three times to Mount Everest.

I said yes even before they mentioned what the expedition would entail and where Khan Tengri was.

Khan Tengri itself played a big role in the decision. It’s the second highest peak in the Tian Shan range and known as the prettiest mountain in the entire region, this perfect marble pyramid rising out of one of the most remote mountain ranges on the planet. The idea of standing there, on a mountain with that kind of presence, while also contributing to scientific work, was impossible to turn down.

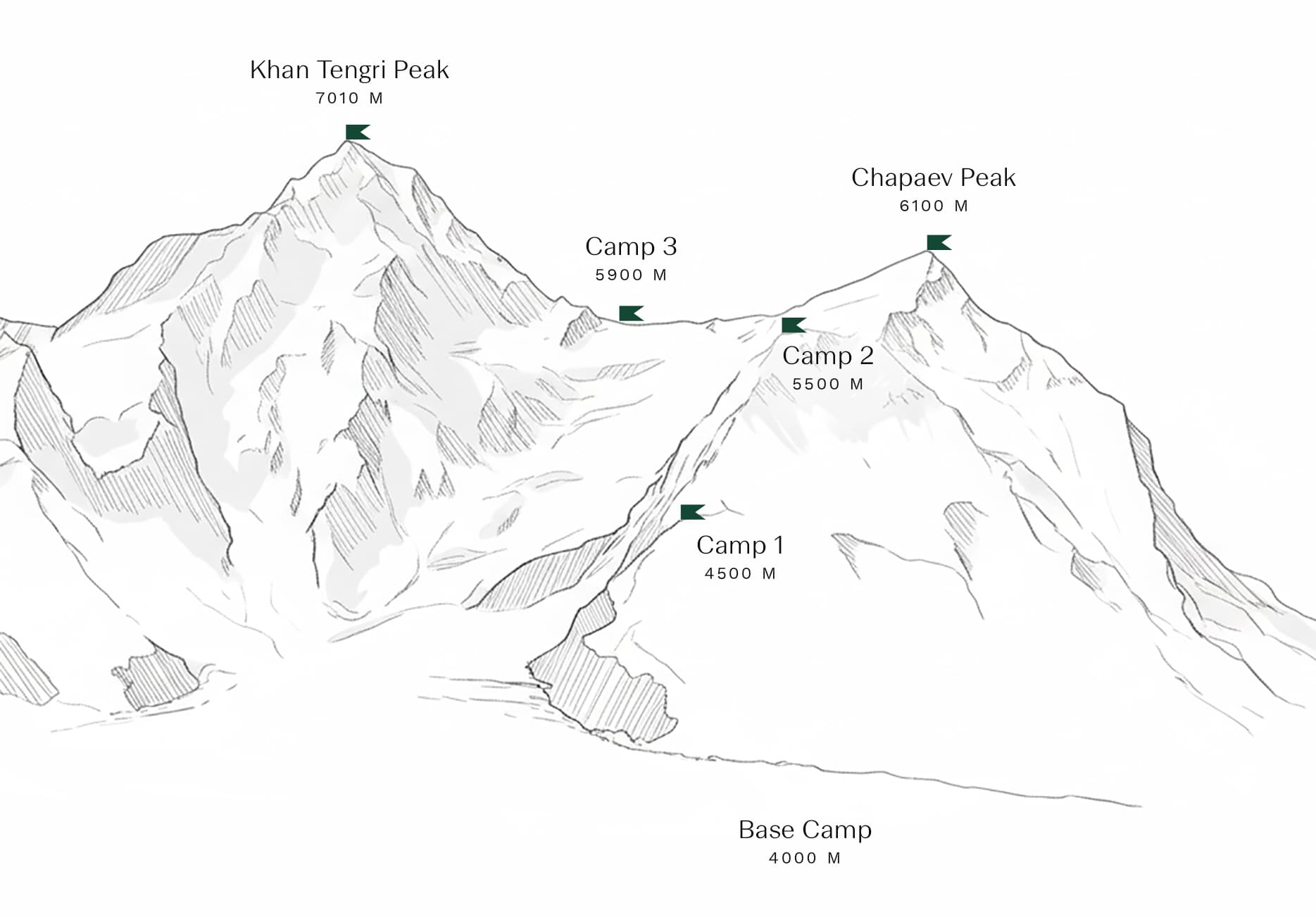

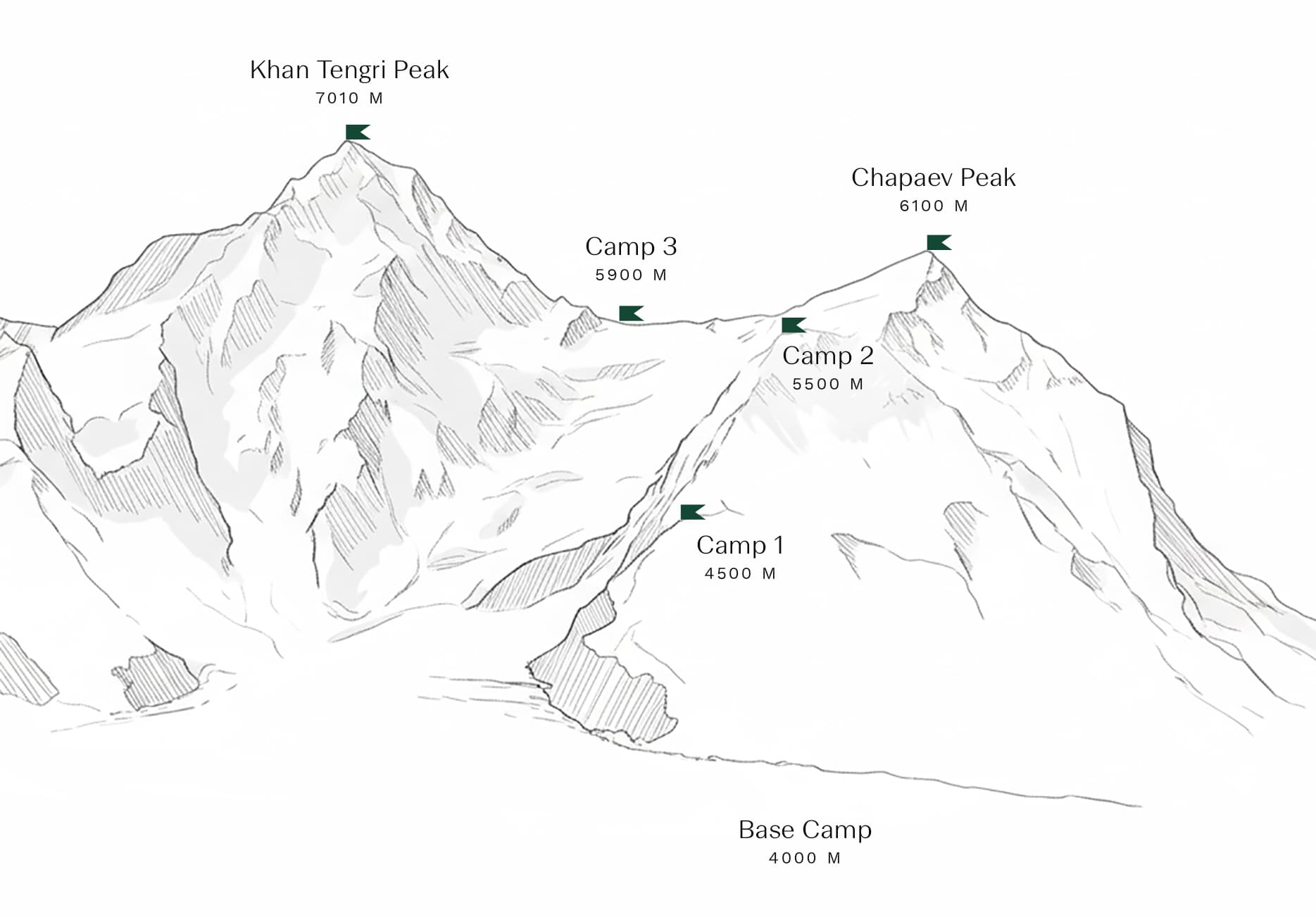

Definitely. The scientific side gave the expedition another dimension beyond just reaching the summit. We were there as part of the American Climber Science Program, collecting snow and climate data in a region that’s changing fast. Khan Tengri sits above one of the world’s largest non-arctic glaciers, the Inylcheck Glacier. As an important source of freshwater for the region, it is all the more important to monitor for climate science.

That added a sense of responsibility, that the climb wasn’t just personal. It wasn’t only about reaching the top, but contributing to something bigger than yourself. The expedition set out with the following priorities:

Safety

Science

Reaching the top

When all three aligned, we were lucky enough to push for the summit.

Those months were special. I had to balance work, training and also financing such a trip. I ended up getting a part-time job staging apartments. Basically the best training you could think of – long days in aerobic pulse zones (zone 1-2), carrying heavy stuff in every thinkable position, often up to the 5th floor with no elevator. It was heavy, but it allowed me to stay positive because I was training for something I really wanted.

In the last four weeks before departure, my girlfriend and I drove down to the Dolomites and the Italian Alps to start my acclimatization as close to departure as possible. The trip started off with the highest peak in the Dolomites at 3,300 meters and ended with several 4,000 meter peaks in the Alps – long days at altitude as well as sleeping at higher elevations.

I eventually made my way back home to Oslo and had two full days to get sorted and pack my stuff before the journey east.

I was born and raised in Oslo, Norway, more specifically Sørkedalen, where you have the local ski resort atop one of the steepest hills surrounding the city. So my journey to school the first 13 years was really dependent on my legs to get back home from school.

After high school, I went into my military conscript service and stayed in the military for six years, working in one of the leading military platoons where I stayed outside for longer periods of time, surviving and crossing all types of terrain. My old colleagues actually just completed 100 days outside, unsupported in northern Norway.

My history in the military has undoubtedly been really valuable for this expedition. Having completed specialist courses such as the NATO Special Operation Combat Medic & the Royal Marine’s Mountain Leader Course, I already had valuable experience with medicine, the cold, long days and climbing. For this reason, I was designated medic for the expedition. But there was still a big unknown factor for many of us on the team. Altitude.

That’s a good question.

Aside from spending a lot of time in the mountains, knowing your equipment and having physical and mental resilience, I’ve learned that big challenges are rarely about strength alone—they’re about mindset and adaptability. Over time, I’ve realized the importance of staying calm when things don’t go to plan, focusing on what’s in front of you, what you can actually control and trusting the process.

Whether it’s in the mountains or in everyday projects, I try to approach things with patience, structure and a sense of purpose. You can’t control the environment, but you can control your attitude, your effort and how you treat the people around you. That’s usually what makes the real difference, up at 7,000 meters and down at sea level.

Altitude, weather and dangers that you cannot do anything about.

Altitude was my biggest uncertainty. But I could not figure out how I would handle it before I was actually in the environment. So the best thing I could do was prepare. With acclimatization, knowledge and training.

I read two books that especially helped me: “På livets grense” by Erik Sveberg Dietrichs and “Training for the new Alpinism” by Steve House and Scott Johnston.

These taught me different methods for acclimatizing, as well the physiology of how the body reacts to altitude and cold temperatures.

Khan Tengri is known for brutal storms and unpredictable weather windows, and once you’re up high, there’s no room for mistakes. I was also aware that it would test the team dynamic, how we’d collectively handle fatigue, decisions and pressure. That’s something you can’t fully plan for.

We were a small international group connected through the American Climber Science Program and the Explorers Club. Climbers, researchers and mountaineers with different backgrounds, but a shared drive to explore. The group consisted of four Norwegians, two Americans and one lady from the UK. The diversity in the team made it interesting, some with more expedition experience than others, but overall a strong team with a common goal.

A lot of the conversations are about conditions, plans and timing. But also small things, like humor and motivation. I naturally tend to step into the role of keeping things calm and organized, making sure we move efficiently without rushing. When everyone’s tired, you need someone who can bring focus and stability.

The highest high was definitely reaching the summit together with Filip, Martin and Pasangdawa Sherpa. No doubt about it.

Although the feeling was not filled with a lot of energy and crazy celebration, it started off as an emotional moment when I first stepped up to the peak. A feeling of mastery and being proud of your own effort. A lot of different things leading up to this moment made it feel even more special. When FIlip and Martin made it to the peak we hugged it out and had a proper think about what we had actually achieved. It was a special moment.

One feeling that has to be mentioned is that you're not really finished yet. In the back of my mind I knew we still had 4-8 hours of descent back down to Camp 3. So you can't really drop your guard 100%.

The lowest low came in the days before departure from basecamp back to Karkara and the airport in Bishkek. A time filled with uncertainty, waiting for weather windows, lack of information and lots of terrible news within a short period of time.

I'm not going to mention everything in detail, but we ended up waiting for six days at 4,000 m at basecamp before being flown out by helicopter due to bad weather and the prioritization of other climbers. When the good weather day arrived, we were certain that we would be picked up. But on that day, the helicopter we were expecting had been used on a rescue operation and ended up taking a super hard landing/crash, breaking the hips of three people onboard.

At the same time, we received news from the staff at basecamp that one of our guides (Alexi) had passed away in his tent at Camp 2. All by himself. He summited Khan Tengri two days later than us with another group, and instead of making his way down to basecamp the day after the summit, he felt tired and wanted to stay one night at Camp 2 before coming down. The rest of the group he was with continued down and basically left him all by himself at 5,500 m. Three days later, he was found dead in his tent.

This was a feeling of meaninglessness. And the fact that Norwegian “Fjellvettregler” (The Norwegian Mountain Code) likely would have saved him, made it even more pointless. You don't leave a man behind. It's that simple.

Despite these unfortunate events that we had no control over, we have to look back on the incredible experience and be proud of our own achievements.

I expected it to be tough, but I didn’t anticipate how technical the climb would be. So I believe the whole group underestimated how tough the route was. For example, the trek from Camp 1 to Camp 2 was 1,000 meters of elevation gain, and you are already at 4,500 m going up to 5,500 m. This segment of the route made three of the people we had in the team turn back and not finish the journey.

Pasangdawa Sherpa joined us for the summit for the first time. When he reached the top he said: “This is so much harder than Everest.” I feel like that really put it in perspective.

The scale of the place also surprised me – it’s truly vast and untouched, which makes you feel both very small and very alive.

Action speaks louder than words.

The three Norwegians that reached the top all did their first 5,000 m, 6,000 m and 7,000 m peak. But through a humble mindset, learning from the people we met on our way, we made it work. In addition, we were able to both secure the samples we needed for the science and reach the summit in a safe way.

At the end of the trip we were simply known all around the mountain as "the Norwegians". Without even talking much to other people on the mountain, the word had spread. We ended up getting the fastest time up from Camp 3 to the summit as a group that season.

The feeling that’s stayed with me the most is how important preparation, being humble and respect for the mountains really are. You can train, plan and think you’re ready, but once you’re up there, you understand how small you are compared to the environment you’re moving through.

Khan Tengri reminded me that good preparation isn’t about eliminating risk, it’s about giving yourself the margin to make good decisions when things get tough. And the being humble part… that comes naturally when you see how fast conditions can change. The mountains don’t care about your plans or your timeline.

Coming home, that respect has stayed with me. It’s made me more aware, and more grateful for both the calm days and the challenging ones.

Right now, it is just the small, everyday adventures. After a big expedition, it’s easy to start chasing the next summit immediately, but I’ve realized how valuable the simple things are – the small missions, the local mountains, the moments outside that remind you why you love this in the first place.

I’m sure bigger expeditions will come again, but at the moment I’m enjoying being present, staying curious and finding that same sense of exploration in the day-to-day. Sometimes the small adventures are the ones that reset you the most.

And I also believe the basic training periods in between are really important to be able to deliver at a high level when you need to. Building a solid base while resetting your mind and enjoying the smaller adventures again.